Back to the future (2005)

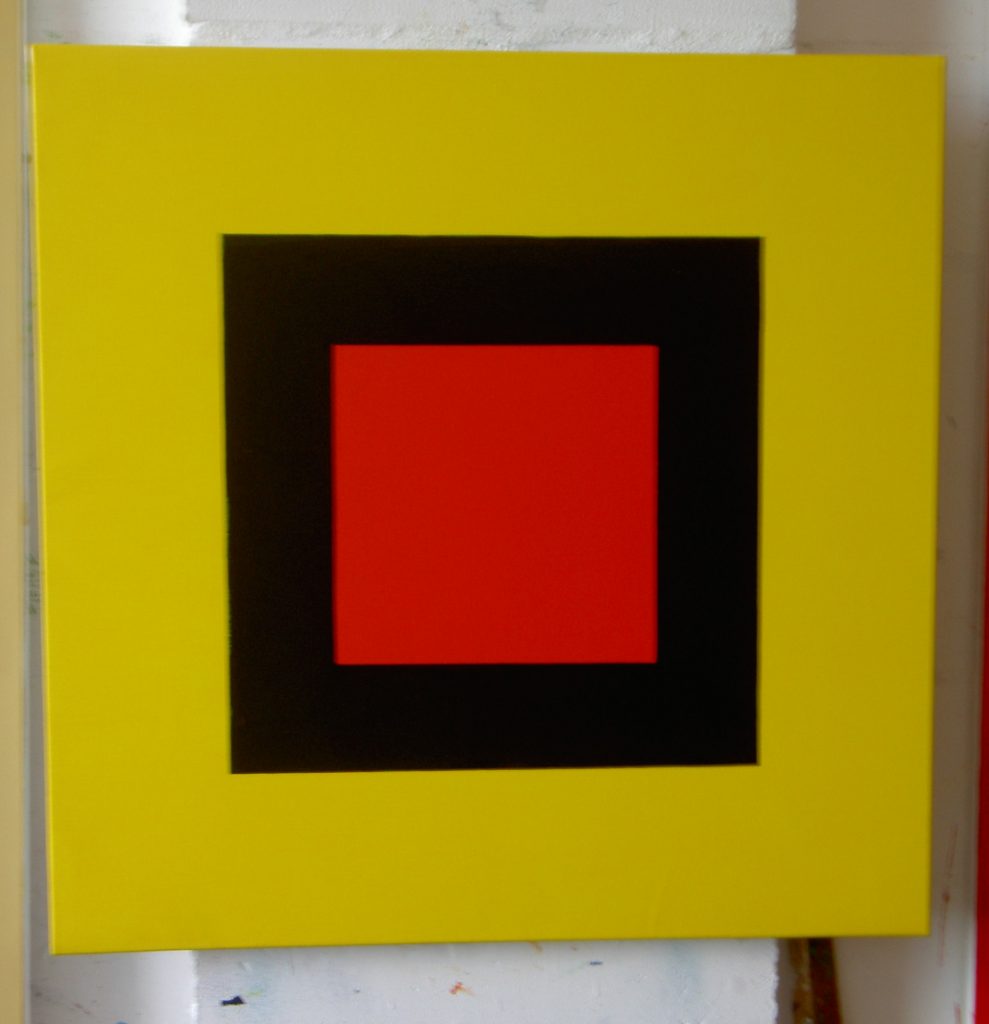

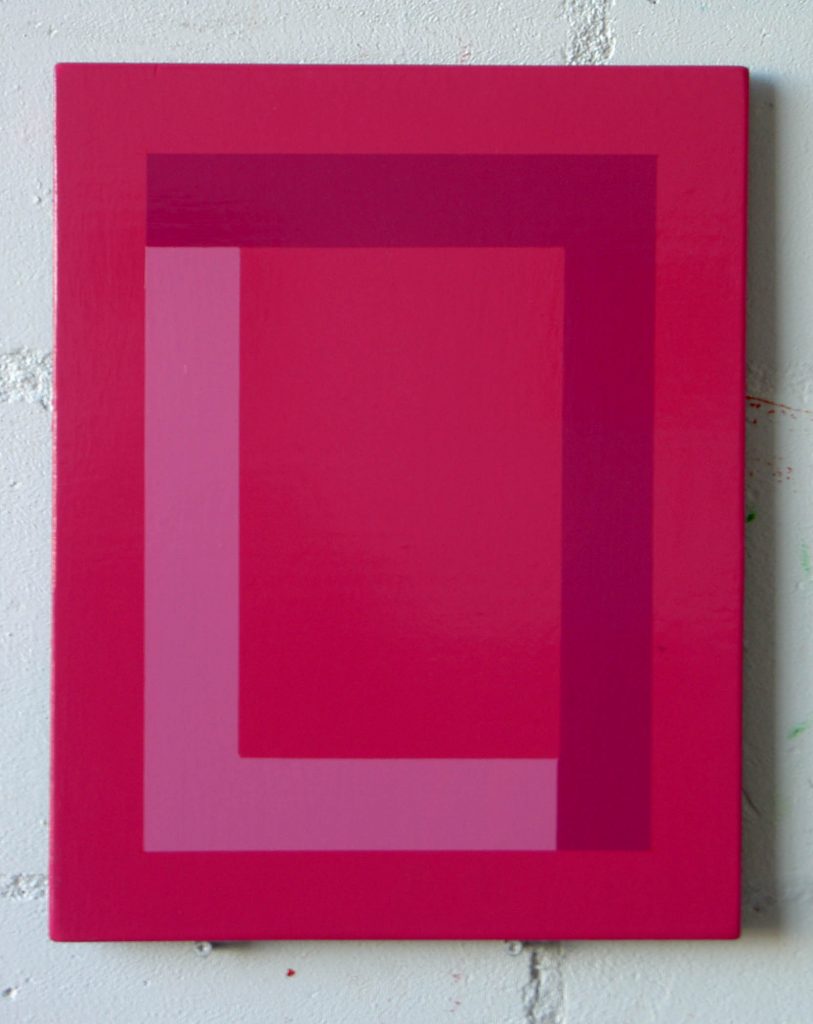

Schematic, limited colour palette, playing cards, 8 colour palette computer games, 18thc French wallpaper cartoons, Disney cartoon backdrops, heraldry, Roman wall paintings, mosaics, magazine layouts, symbols, logos.

I wanted a constrained colour palette;

Use of colour combinations that commonly crop up; in nature, advertising, flags, competing associations.

Corporate hijacking of specific colours, and through a constant bombardment triggering an association even without a logo in view. Sometimes I use these latent associations, as a base material in itself. How a specific association conjures up an intense world of its own in relation to the painting, that is quicly shattered when another possibility is considered. Mental resonance of associations, and the dialogue between them.

What are triggers a response. Personal associations related to a specific time, place, culture, associations that could be seen as global, and transcending geo-temporal. Hard-wired associations.

Modernist painting went to great lengths to divest itself of any suggestions of illusion. I’ve always embraced comments that a such-a-such painting ‘looks like……’, the process of recognition in the face of an abstracted image, or with a paucity of information is interesting in itself. Vitality, quick-fire recognition.

The viewers shifting thoughts and responses in relation to the fixed image. Circuitous, oscillating

Format that loosely applies a horizontal/vertical format in the composition.

Simplified forms, with a limited palette, suggestions of light and shadow, perspective, highly stylized rendering of objects.

Modern Warfare (2004)

War is played out in military computer simulations with the use of artificial intelligence representing the enemies’ movements; with accurate 3D representations of hostile territory, and with software emulating the conditions and consequences of any actions taken on the battlefield. Data sourced from Global Positioning Satellites and reconnaissance drones is fed into virtual 3D models that describe the geography of potential areas of conflict. This information is utilized in different ways: surveillance, military training, and in actual conflict to guide ‘smart bombs’ at specific targets. The use of computer simulations as a tool in real combat has been used to devastating effect in both Gulf wars, revealing how both the computer model and its real counterpart can have a reciprocal effect on each other.

A few decades ago, the software needed to run simulations on this scale required super-computers such as CRAY mainframes. This level of cutting-edge hardware was only accessible to government departments and the academic world. Now, the technological gap has steadily closed to the point where many aspects of military simulations and computer games are indistinguishable from each other. There is also much more exchange of knowledge between the military and the commercial world. It is just as feasible for a software engineer previously involved in classified military projects in the ex-Soviet Union to be working for Microsoft, as it is for a games company to be consulted, or sub-contracted to create software for military simulations.

Most first-person shooter games could share the same underlying technology, they will use 3D engine technology, physics systems, levels of artificial intelligence, animation systems, along with lighting, camera and special effects routines. In terms of game mechanics, the player has an optional first-person camera view, will possess or be able to acquire a range of weaponry, and progress through a series of missions/challenges/skirmishes/fights. First-person shooters could be the gothic horror of Sega’s House of the Dead, a B-movie inspired laboratory, straight combat simulations like Medal of Honour and Desert Storm, or combat set ‘in the near future’ (usually an exaggerated present with plenty of high-powered weaponry). Historical themes, Sci-Fi, and fantasy are used, and often mixed as influences in the first-person shooter.

The wide cultural impact of video games has gradually changed the way military personnel engage with military computer simulations. Military recruits are likely to have grown up playing console games. On-line combat games such as Quake or Half-Life further breakdown barriers between the military and civilian spheres; both could be fighting against each other, or working as a team in an on-line tournament. There is also the recent development of professional games players skilled enough to make a living solely from winning on-line competitions, and selling virtual commodities accumulated during play.

The general perception of armed conflict is likely to alter with increasing exposure to military sims and home-entertainment games. Video games will often test our split-second reactions to hazardous situations that most of us are never likely to encounter in real life. Players are actively engaged in video games, requiring the player to make a whole host of decisions on different levels. This is in contrast to the more passive experience of watching a film where the viewer follows a prescribed sequence of events unfold. Though it could be argued that games are scripted –for example, on turning left into specific corridor you will always be met by the same two zombies- there is plenty of scope for the player to react and respond to the challenge in different ways, leading to many possible outcomes that, in turn, effect the course of play in the game.

Developments are leading to a scenario of remote centres where ‘combatants’ would operate robot counterparts on the battlefield located elsewhere using cameras, virtual environments, and remote-control control mechanisms. The video games ‘professional player’ would be an ideal recruit to engage in a war via computer terminal, where physical distance from the battlefield would have little relevance. Military use of technology and computer simulation has the potential of further disengaging the combatant/operator from the realities of the battlefield.

Nightwatch

Low-resolution night footage supplied by reporters during the Iraq conflict reduced Iraq to a nightmarish landscape saturated green. Viewers dominant perception of the conflict was formed through these pixelated ‘night goggle’ images.